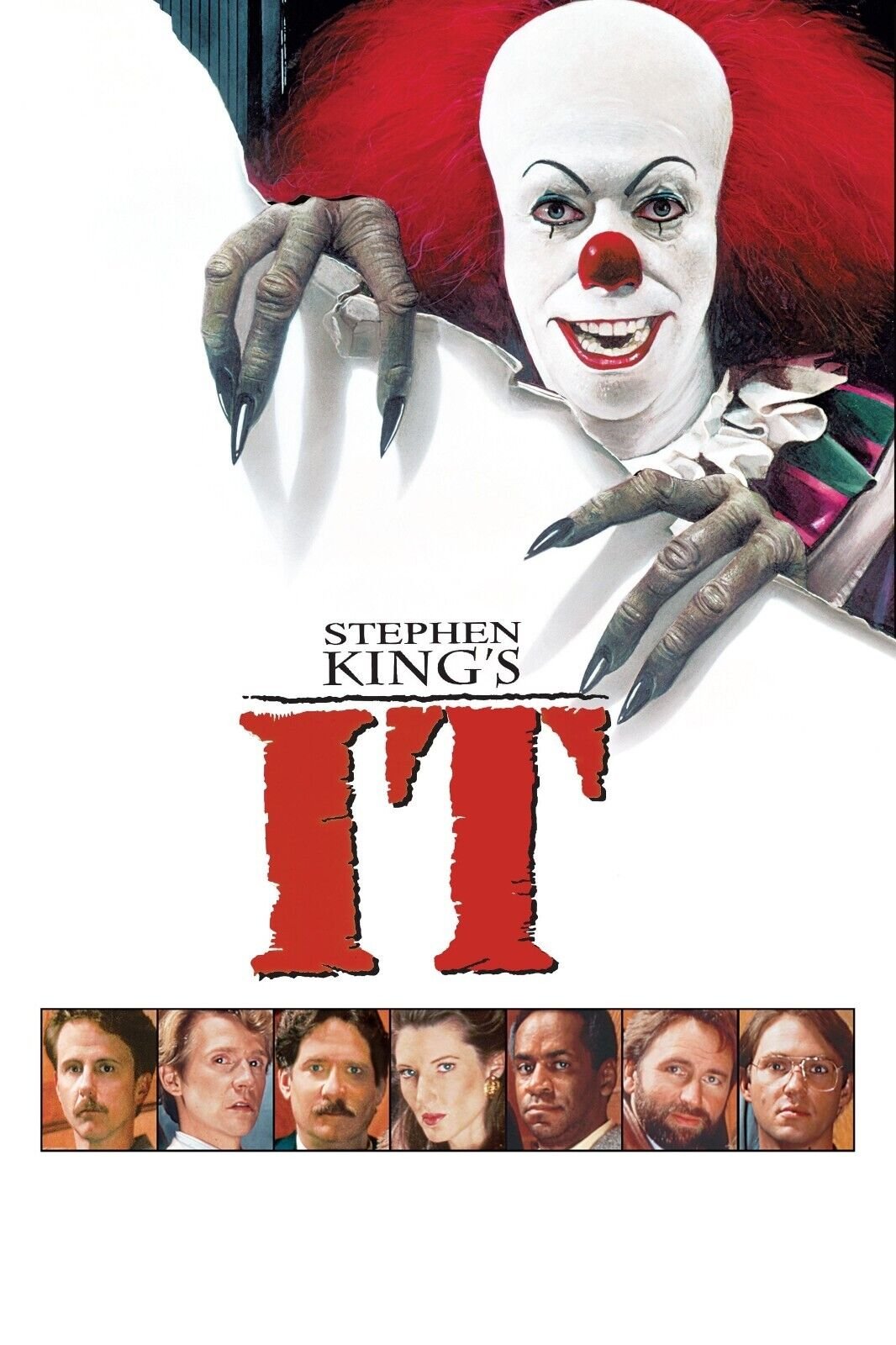

It (1990)

My mind is fogged as well. When Stephen King’s It came out in 1986, I was the age of the kids in the novel. By the time the 1990 TV miniseries came out, I was a full-on teenager near the end of my initial run with King’s work (1991’s Needful Things would be the last one I read when it came out, after reading just about every book he’d written since 1981). I continue to age beyond the adults in the story’s present day, though the actors who play them in the original series remain older than me, just as the characters were in 1990. It was a disorienting surprise to remember that Emily Perkins plays young Beverly Marsh, ten years before she became Brigitte Fitzgerald in Ginger Snaps—did I already know this actor before I saw her in my favorite movie from 2000, and did that predispose me to identify with Brigitte?

All of this flashback confusion gets twisted into my experience of the novel and its adaptations. It’s unclear if my first memories of It are of the book or the series. About a year ago I read the novel—which set off a personal Stephen King revival in which I filled in some of the older books I might not have read before, then got into his more contemporary novels, including 2023’s fantastic COVID-era gumshoe thriller Holly—and couldn’t say for sure if I read It back in the day.¹ I do have a teenage memory of being disappointed by the giant spider. That could have been an impression of the novel or the series, though having revisited both, I’d say the TV spider is the bigger letdown. The specific impression I recall is something like After all that, it’s a big toy bug?

Not only is the TV spider a dud, the series misses all of the nuance of the novel spider. Like, not only is It a clown that’s also a spider: Pennywise is a mama spider, baby. When we think about the novel today, we can read It as trans, and trouble the heck out of that possibility (trans figure as ultra-powerful monstrous other and formless fear itself).² While Tim Curry as Pennywise suggests a queer (if not trans) reading of the series, the dumb glowy totally not preggo TV spider doesn’t give us any gender stuff to chew on. Beyond It’s potential juicy fluidity, the novel also gives us a trail of eggs, and the possibility that they don’t all get stomped out. The series doesn’t fuck with that, either. It’s fun anyway, and really doesn’t drag through the 187 minute run (according to the DVD packaging—it’s listed elsewhere at 192 minutes, to further warp the timeline), even if the stagey TV acting, fuzzy dialog, and awkward early ’90s costume and hair can be devastating to sensitive viewers. The ’80s hangover vibe comes through the wooziness of characters who stay drunk for most of the film, and John Ritter confounds as always by being both incredibly smarmy and totally likeable.

How does the more recent movie series treat the gender web and update the special effects and fashion, and does the story timeline get as compartmentalized and dumbed down as I recall? The fog thickens: we’ll have to wait for Mike Hanlon’s call to wake up those memories. 3 out of 5 sacs of blood.

¹ Another way back to King’s work was teaching a speculative writing class called I Was a Teenage Monster at UPenn, where we start by talking about what we like to read—folks, Stephen King is still alive in the minds of our next-generation horror writers. Then there’s Fangoria’s Kingcast pod, where hosts Eric Vespe and Scott Wampler bring on guests like CDSOB house favorites Stephen Graham Jones, Karyn Kusama, The Boulet Brothers, and Guillermo del Toro to talk about their formative experiences with King’s novels and film adaptations. And perhaps most crucial for providing a model critical perspective is Meg Elison’s “All the King’s Women: the Fats.” Our developing sense of horror poetics owes much to Elison’s ability to call out what she doesn’t love about the horror writing she loves, and point the way to better horror writing to come. Indeed, Elison is one of the people who is writing it.

² We can also contend with one of the novel’s opening scenes, and its representation in 2019’s It Chapter Two, where Pennywise intervenes on the homophobic assault of a gay man only to murder the victim. King has a complicated history in his representation of queer characters, which is explored in the “Queer for King” episode (#149) of Kingcast.

—J †Johnson